The exhibition at Ryugaheon Gallery marked my fifth trip to

Seoul in as many years. The

gallery itself is known to photographers but not always to a larger

audience. It sits tucked away in a

little alley that is reached after a fairly labyrinthine walk through the back

streets behind the old Imperial Palace.

When you arrive, you enter into a tiny zen garden with

gravel underfoot and rough hewn wooden benches. Built in the traditional hannok style, the gallery itself

feels more like a modest temple or a forest shrine than an art space per se. Clusters of tiny yellow flowers sprout

here and there on its tiled roof.

On one side of the garden is a bookstore and café. Beyond that, there’s an office and a

workshop. On the other is the

entrance to the exhibition area.

Having this show in Seoul changed my relationship with the

city in an essential way. It’s

hard to describe the feeling of belonging that comes from having your

photographs on display and being able to bring friends to visit day after day. It’s like welcoming them into your

house. As if you’ve set up

residence there. Not only that,

but friends bring friends and -before you know it- your circle has expanded

dramatically to include all kinds of interesting people.

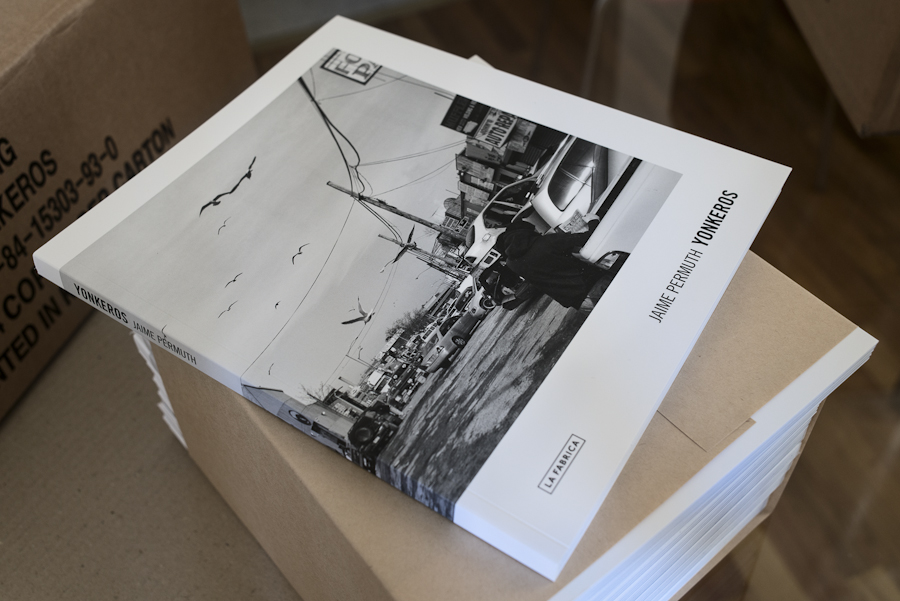

But of course, the greatest pleasure is seeing the work in a

new context and hearing back from local audiences. It was a long journey indeed for the Latin American

mechanics to make: not only from Willets Point -but from their countries of

origin. Perhaps because of Korea’s Buddhist roots, many people remarked on the passing of the seasons in

these photographs and the way the light and the elements redefined the

landscape depending on the time of the year. Others compared Willets Point to neighborhoods in Seoul,

which have –or perhaps more interestingly once had- a similar feel. One particularly perceptive man noted

that the passing of the seasons underscored the useful life of machines and how

everything in the world has a cyclical duration.

On two separate occasions, my Korean mother in law organized a

large group of friends to come and visit the exhibition. I especially enjoyed these visits

because the ladies dressed up in their finest and made a day out of it. They really enjoyed themselves. And as such, they lingered, spoke from

the heart and felt free to reminisce.

One woman responded to an image of a small stack of tires covered in

snow with a childhood memory of her own, remembering the large earthenware jars

of kimchi sitting in her mother’s yard during the winter months. Hearing that was a modest epiphany; I

felt like the image had translated beautifully and poetically in a most

unexpected manner.